FULL BIOGRAPHY

Norman Houstoun O’Neill was born in London on 14th March 1875, the youngest of six children of the successful Irish artist G. B. O’Neill (1828 –1917) and Emma O’Neill (née Callcott, 1838 –1913) who was descended from two generations of composers. His early education was at home and at local private schools in Kensington, London. As a child he became acquainted with the colony of artists that centred on Cranbrook in Kent where his father had another house. In London he was often taken by his father to the theatre and in his painting The Rehearsal G. B. O’Neill depicts his family watching amateur theatricals with the infant Norman O’Neill standing beside the proscenium arch. From the age of 14 he had lessons in theory and composition from the composer Arthur Somervell who was a neighbour. He had encouragement from The Times music critic J. A. Fuller-Maitland, and through one of his mother’s relations he was introduced to the renowned violinist and friend of Brahms, Joseph Joachim, who recommended that at the age of 18 he went to the Hoch Conservatorium at Frankfurt-on-Main to study composition with Iwan Knorr. Another influential figure at home was the Swedish poet Count Eric Stenbock (through whom he met Aubrey Beardsley) who at his death in 1895 left Norman a substantial legacy of £1500 towards his musical studies, enabling him to stay on for his final year at the Frankfurt Conservatorium. There he met up with fellow-students Balfour Gardiner, Roger Quilter, Cyril Scott and Percy Grainger who collectively became known as The Frankfurt Group. At Frankfurt it was through Cyril Scott that Norman became briefly acquainted with the poet Stefan George, but a more lasting friendship was struck up with another pupil of Knorr’s, the German composer Clemens von Franckenstein who was for a while to be conductor of the Moody-Manners Opera Company in England.

While at Frankfurt Norman was recommended by Knorr as a suitable teacher of harmony to a young English student who shared a pension with Adine Rückert, a French student, the two girls being piano pupils of Clara Schumann. As Adine’s harmony teacher spoke neither English nor French, she soon became Norman’s second pupil and, with a shared interest in music, art and literature, a close friendship soon developed. When Clara Schumann died in 1896, Adine returned to Paris but the two met regularly either in London or Paris or on the Continent.

Amongst Norman’s earliest compositions were some songs sung at a Conservatorium concert in March 1896 that had a favourable review, a cello sonata, and Variations on Pretty Polly Oliver for violin, cello and piano. On completion of his Frankfurt studies he returned home in September 1897, living in his parents’ new home of 18 Victoria Road and supplementing his income by teaching piano and harmony. Adine meanwhile settled into a career as a pianist, introducing in her first public recital in Paris in February 1899 Norman’s Variations and Fugue on a theme that she (A. R.) had written. They were married in July 1899 at Neuilly, a suburb of Paris, and spent their honeymoon in the Black Forest. Their married life began at 7 Edwardes Square in Kensington. Together they gave two chamber concerts at the Steinway Hall, in November 1900 when a new string trio op. 7 was introduced, and in December when the Variations and Fugue were well received. Adine also started some private teaching.

Norman’s first important orchestral work was the overture In Autumn dedicated to Henry Wood and conducted by him at a Promenade concert at the Queen’s Hall in October 1901, and soon taken up by Hans Richter in Manchester. That same year came a significant commission, on the recommendation by his brother Frank who worked in the theatre: to write incidental music for John Martin-Harvey’s production of After All (based on Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s 1832 novel Eugene Aram) for which he composed two songs, and The Exile (Lloyd Osbourne and A Strong) which included a march.

In February 1903 Adine gave a chamber concert at the Steinway Hall consisting entirely of works by Norman, including the first performance of his Piano Quintet in E minor. His ballade for contralto and orchestra Death on the Hills was given at the Proms in 1904. Another and more substantial theatre commission was music for Martin-Harvey’s Hamlet first staged in Dublin in November 1904, but before that in October the overture Hamlet was heard at the Proms under Henry Wood. That year also saw the first performance of the Variations and Fugue on an Irish Air (Moloch Mary) for two pianos, later orchestrated and performed at the Proms in 1911 under Henry Wood.

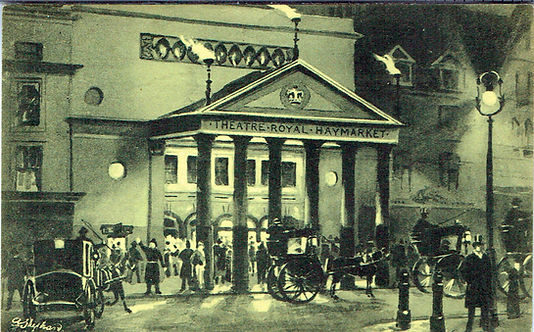

In 1903 Adine was offered the position of head music mistress of St Paul’s Girls’ School in Hammersmith (in 1905 she appointed a young Gustav von Holst to the staff), and in 1904, after the birth of a son, Patrick, Adine and Norman moved to 4 Pembroke Villas in Kensington which remained their home. In 1906 his overture In Springtime was played in Birmingham and at the Proms, and a number of his works were now published by Schott & Co. More theatre commissions followed, sometimes with Norman conducting, although in 1907 his friend Clemens von Franckenstein conducted the run of A Tragedy of Truth at the Aldwych. In 1909 Norman took Henry Wood’s place to conduct in Paris a choir of one hundred London schoolgirls as part of an Anglo-French festival, orchestrating eight national songs for the occasion. That year he became Musical Director of the Haymarket Theatre, London, a position he was to retain for twenty-two years, resulting in a life-time’s work of writing for the theatre and Norman O’Neill becoming in his day one of the best-known composers in the field, providing incidental music for nearly 50 productions. The two most successful scores were for the first English production of Maurice Maeterlinck’s children’s fairy play The Blue Bird in 1909 from which the popular orchestral suite was published by Elkin, and for J. M. Barrie’s ghost play Mary Rose in 1920. Barrie, like Maeterlinck, was at first doubtful as to whether music was at all necessary, but in due course he became most approving of O’Neill’s score. He even described the music’s effects in the first published version of the play, effectively giving it the author’s imprimatur. Remembered especially for its haunting call at the end of Act II on which the music is based, its dramatic impact in a performance of the play must have been remarkable. The music for both The Blue Bird and Mary Rose was recorded by Columbia conducted by the composer.

Norman was by all accounts a very kind person, with a good sense of humour and, according to Scott, ‘blest with the most striking good-looks and great personal charm’, and distinguished from the age of 21 by his snow-white hair. He was a great organiser and a firm but fair disciplinarian and an active member of a number of important music organisations at that time, holding key positions with many of them. He joined the Society of British Composers and the Musical Conductors’ Association, and played a significant role in 1908 in the formation of the short-lived Musical League of which he became secretary. Elgar was president, and the vice-president was Delius whom Norman first met in 1907, becoming one of the composer’s closest friends. Delius was usually a visitor to Pembroke Villas on his occasional trips to England, and in December 1907 Norman made the first of his visits to Delius’s home at Grez-sur-Loing. When Delius came again in June 1909 for the first complete performance of A Mass of Life he stayed with the O’Neills, and in July Norman went on a walking holiday with Delius in the Black Forest. Much later it was O’Neill who persuaded Delius to allow James Gunn to paint him, resulting in the familiar portrait of the blind and paralysed composer in his last years.

Norman’s setting of Keats’ La Belle Dame sans Merci for baritone and orchestra was first performed at Queen’s Hall in 1910, with Frederic Austin the soloist and the composer conducting. La Belle Dame sans Merci and Introduction, Mazurka and Finale (based on dances from the ballet A Forest Idyll and first heard at a Royal Philharmonic Society concert) were performed at the Balfour Gardiner concerts at Queen’s Hall in 1912 and 1913, principally of British music. When the final concert seemed likely to be cancelled because of Gardiner’s dispute with the orchestra, it was Norman who intervened and settled matters. Gardiner was a close and generous friend and in 1928 Norman dedicated to him the first of Two Shakespearean Sketches.

Varicose veins in the legs made Norman unsuited for war service, but he was often involved in conducting for war charities and he proved an invaluable member of the Royal Philharmonic Society, particularly in the engagement of players. He had been elected associate in 1912 and soon became honorary director and in time honorary treasurer. In January 1916 a daughter, Yvonne, was born, and at his own suggestion Delius became her godfather. In May Norman opened the Shakespeare tercentenary celebrations at Drury Lane with his Hamlet overture. In 1918 for six months he rented a house in Shere, near Guildford in Surrey, and enrolled there as a stretcher-bearer, meeting the wounded soldiers when they arrived by train. That year he took over the St Paul’s Girls’ School orchestra while Holst was abroad organising music for the troops in the Near East.

The success of Mary Rose which opened in April 1920 led to a commission to write music for David Belasco’s production of The Merchant of Venice in New York for which he sailed to Quebec in 1922, travelling through Canada and America and supervising the music for the opening night. In 1924 he joined the staff of the Royal Academy of Music, teaching harmony and composition. He was also an examiner for the Associated Board. That year he bought Losely an Elizabethan farmhouse in Surrey that he kept until 1930. Although he did not find composing in the country easy he did write his scena The Farmer and the Fairies there which was performed for the BBC firstly by Henry Ainley in 1931 and later by Christopher Hassall in 1951.

In 1929 he was united (with the exception of Gardiner) with the Frankfurt Group whose music was well represented at a festival of British music at Harrogate where Norman conducted his Festal Prelude ‘The White Rock’ and ballet music for Alice in Wonderland. In 1933 Norman made a contract with Stoll to write music for a series of Shakespeare plays to be performed in London and his entirely new music of this time for Henry V has recently been rediscovered in the Royal College of Music. In February 1934, crossing the road to conduct a programme of his Shakespeare music at Broadcasting House, he was struck on the head by the wing mirror of a passing three-wheeled vehicle. Blood poisoning set in and on 3 March he died, 11 days short of his 59th birthday, in that same fatal year that also saw the deaths of his two friends, Delius and Holst, and of Elgar. Beside his extensive music for the stage sadly neglected today, Norman left a comparatively small output, but it includes some delightful orchestral works, choral works, a number of songs, and some fine chamber works several of which have been issued on CD; music that is always melodic and well-structured and deserving of a more frequent hearing. A revised edition of the definitive biography by his son-in-law Derek Hudson, Norman O’Neill – A Life of Music, first published in 1945, was issued in 2015.

Stephen Lloyd

Portrait of Norman O'Neill

Portrait of Norman O'Neill

Hoch Conservatory/Dr. Hoch's Konservatorium,1900 (source: Wikipedia)

Norman O'Neill, 1903

© The Michael Diamond Collection / Mary Evans Picture Library

Letter from Delius

Garden at 4 Pembroke Villas, Kensington

Norman O'Neill gardening at Losely, 1930

Norman O'Neill, aged 53